Liberated by the revolution and empowered by military victory, they would now become the masters of their lives and collective masters of their country. In the eyes of DK’s leaders, Cambodia’s poor had always been exploited and enslaved. Family life, individualism, and an ingrained fondness for what they called ‘feudal’ institutions, as well as the institutions themselves, stood in the way of the revolution. They sought to transform Cambodia by replacing what they saw as impediments to national autonomy and social justice with revolutionary energy and incentives. The leaders of DK, who were members of Cambodia’s Communist party, called themselves the ‘revolutionary organization’ (angkar padevat). No Cambodian government had ever tried to change so many things so rapidly none had been so relentlessly oriented toward the future or so biased in favor of the poor. So had money, markets, formal education, Buddhism, books, private property, diverse clothing styles, and freedom of movement.

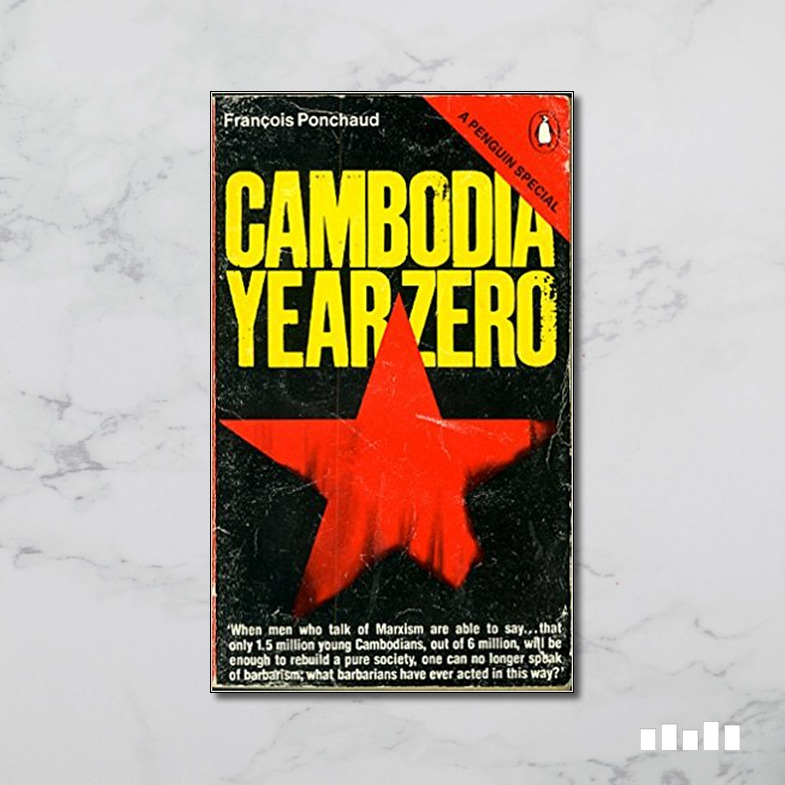

The revolution it sponsored swept through the country like a forest fire or a typhoon, and its spokesmen claimed that ‘over two thousand years of Cambodian history’ had ended. The Communist regime that controlled Cambodia between April 1975 and January 1979 was known as Democratic Kampuchea (DK). Because of the ferocity with which Cambodia’s revolution was waged and the way it contrasted with many people’s ideas about prerevolutionary Cambodia, it has also fascinated outside observers. For nearly all Cambodians in the 1990s, however, the three and a half years that followed the capture of Phnom Penh in April 1975 were a traumatic period in their lives.

It is uncertain that historians of Cambodia a hundred years from now will devote as much space to the country’s brief revolutionary period as to the much longer, more complex, and more mysterious Angkorean era.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)